Last of a Dying Breed

The retirement of a beloved pastor, and the gradual loss of a generation of leaders

If you attend mass, and you should, at St. Charles Lwanga Catholic Church (formerly St. Cecilia) on the west side of Detroit, you’ll likely park across Stearns street in the parking lot between the former school, now abandoned, and the gym. The gym, nicknamed “The Saint” is a tiny brick hotbox with no windows and no AC where everyone from Magic Johnson and George Gervin to Draymond Green and Devin Booker have played, and where NBA and college players still make their way every summer. I used to go in and watch once in a while and it would get up to well over 110 degrees in there. Just packed with people. Gotta stay hydrated. It’s more famous, in its way, than the church.

You’ll cross Stearns and enter the church through a side door, likely greeted by an elderly black man or two in a red usher’s jacket. When you walk into the sanctuary the first thing you’ll notice is the massive painting at the front of the church of a black, afro sporting Jesus. A beautiful and meaningful piece that is famous in it’s own right, and once graced the cover of Ebony magazine. Next you’ll notice how dark it is, and the smell of the incense. And, unfortunately, you’ll notice how empty most of the pews are.

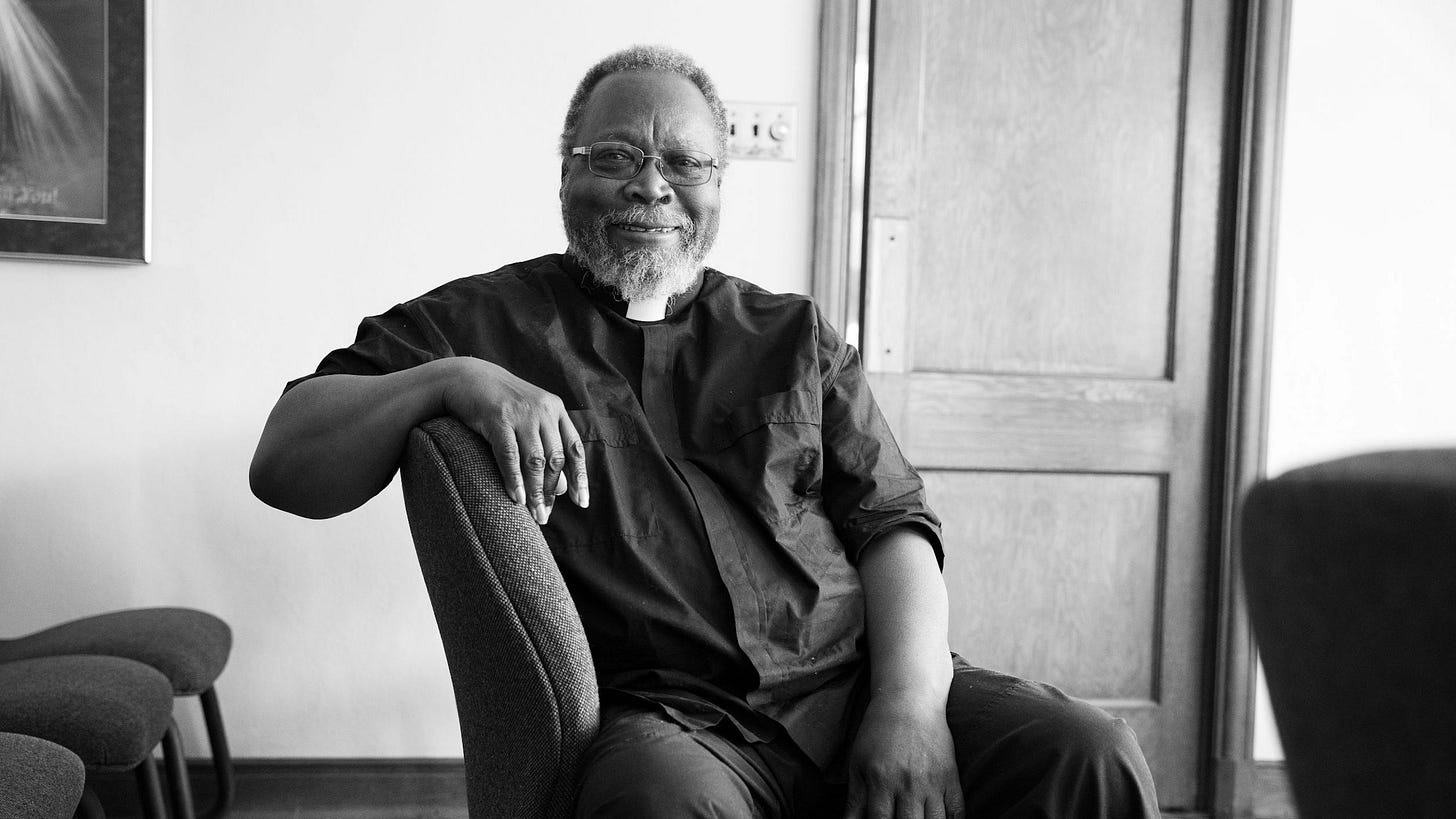

When mass begins the procession will be led by women and children, all of them black. In fact, this church is a Black Catholic church, with a congregation that is probably 95 percent African-American. Bringing up the rear of the procession will be Father Ted Parker, a black man in his late seventies with salt and pepper hair and a gray beard that lends him a certain authority. He’ll make his way to the pulpit and bellow in his baritone: “GOOD MORNING!!” and the parishioners will respond in kind. When he begins to speak you will be struck by his warmth and gravitas. After mass as you leave he’ll shake your hand, thank you for being there, and look deep into your eyes so you know he really means it. All of this will happen, at least, if you go to mass before July 13th.

Father Ted Parker is retiring.

Father Ted Parker is retiring and that’s a good thing for him (he’s been a priest for over 50 years, and he deserves it), but a bad thing for us, bad for the world. And it’s made me sad and nostalgic.

Father Parker is not a famous guy, even for a parish priest. You’ve likely never heard of him, unless you’re heavily involved in the black catholic community of Detroit. But he is an important guy. Important to thousands of people in Detroit. And important to me.

My first job (internship really) as an organizer was working out of St. Cecilia’s. I was 23 and an atheist/agnostic/typical 23 year old. I was trying to figure out what I believed about the world and God and faith and everything else. Obviously, this is not an unusual thing to be doing at age 23 but one of the joys of being 23 is feeling wholly unique, that nothing like this has ever happened to anyone else. I would spend whole days in Fr. Parkers rectory, doing 1-1’s with his parishioners and making phone calls. In between all this, Fr. Parker would come check on me, bring me a cup of coffee or glass of water. He was always comfortable and it was sort of shocking to see a priest in basketball shorts and a t-shirt, but why shouldn’t he have been, I was literally sitting in his kitchen. On many a winter evening I’d sit with him and talk as the skies turned purple and the streetlights flickered on. I had a lot of questions and he had a lot of patience. I think he was sort of bemused to find me, this young, rural, white kid with no idea about theology or even basic worldly stuff, let alone what I believed, sitting in his kitchen daily. But it was a loving bemusement and we found ourselves stumbling into something like a tutor/tutee relationship. I’d think of questions all day, questions about theology (how can God allow so much suffering?). Questions about what it was like to be a priest. Questions about Detroit, and black culture. A lot of them were questions about the nature of God. Then we’d sit and talk about them. Sometimes he’d have answers and sometimes he wouldn’t. He never pretended to know the whole truth, and he never made me feel stupid, young, or naive, even though I was all three.

This went on for about a year. Father Parker was more responsible than anyone besides my wife for shaping my (return to?) faith. I eventually joined a different parish on the east side of Detroit, wonderful in it’s own way, and with another great pastor. But it was Fr. Parker who got me to that point, bringing me into the mystery and joy and hope and tragedy of the church, the community of believers and sinners, the swirling tensions and miracles of parish life. As he did for so many others. As he still does, no doubt, today.

The thing that bums me out is not that Father Ted is retiring. Even then, 12 years ago, he was understandably tired. I can picture him out in the mountains somewhere, or maybe walking through the woods living a quite life of prayer and reflection, away from the banal stresses of administering a struggling parish for whatever time he has left on this earth. It’s what I hope for him. No, I’m bummed because there are so few Father Teds left. And there are even fewer new ones coming, I fear.

Father Parker grew up in the Marcy projects in Brooklyn, to parents fleeing segregation in the South Carolina (there’s a good article about him and St. Cecilia here). One of the things we would talk about is how he decided to join the priesthood way back then. How he admired the local priests in his neighborhood, not for their wisdom or their prayerfulness so much as for their devotion to their people, their commitment to the causes of their people, and their constant presence at the center of neighborhood life. This was a time, remember, when clergy were marching on the front lines for civil rights, something Father Parker looked up to and would begin to do a few years later as a young priest. It was also a time when a priest was looked at with admiration and respect, way before the abuses of children became public, as well as the Catholic hierarchies attempts to cover them up. “Now” Father Parker once told me “when I wear my collar in public most people look at me like a monster”. Not what he signed up for.

What he did sign up for had a lot to do with ministry to a diverse set up people. He joined the Croziers after meeting a black Crozier brother and his first parish call was in Harlem, serving a congregation of with a healthy mix of black and latino families. He took the call at St. Cecilia’s in 2001, in many ways a lifetime ago, a time when the whole city of Detroit seemed like it might fall off the face of the world. He was struck, he once told me, about the way many of his parishioners spoke about the ‘67 riots as if they had happened “last week”. He’s served his parish faithfully for 23 years now, as the neighborhood around it has emptied out and been beset by drugs and violence. The zip code St. Cecilia is in is regularly among the most violent in the U.S. according to FBI statistics. (When I was there it was the most violent, a fact I didn’t know until years later. I never felt unsafe). The memo about Comeback City has yet to reach Grand River and Livernois.

In all that time, this parish, 99 percent black, mostly poor or working class, mostly elderly, has served it’s neighborhood the best way they knew how. Usually with Father Parker leading the charge. St. Cecilia's is known as a place you can show up for help. Even at your most broken, even those shunned by society. They will be met with warmth and brotherhood, by Fr. Ted and his flock. The last time I went to mass there, last summer, I exited and was chatting with Fr. Ted, introducing him to my sons, when a homeless guy began to pull down his pants to urinate on the side of the church, 5 feet from us. Fr. Ted stopped him, took his arm…”not here Anthony. Not right now. Why don’t you go across the street?” Anthony did just that. The fact that Father Parker was on a first name basis with the guy didn’t surprise me, having spent that time with him all those years ago. There was a constant parade of people at his door seeking some kind of help. Some of them parishioners, most just neighborhood people. And Father Ted always helped as much as possible, even though he never felt it was enough. But what can one parish priest do in the face of economic forces beyond all of our comprehension? When his neighborhood is going through a slow motion apocalypse? In the face of a system that would happily throw his whole city and everyone he loves to the wolves?

So he did what he could.

My first organizing campaign ever, forged in those 1-1’s at age 23 in the rectory, was an effort to keep the city from closing the library branch next door to St. Cecilia. A humble but worthy campaign. The residents of the neighborhood felt it was important because the school bus would let kids off there after school, and it gave them a safe place to hang out. So we loaded up a couple vanloads of people. The parishioners (and me) wore purple St. Cecilia shirts. Fr. Ted wore his collar. And we went downtown to the library board meeting. Those guys were pretty surprised to see us, and they shortly after voted to keep that library branch off the list of closures. We held a “rally” in front of the library branch to celebrate, and the Detroit News came out. We were all happy, and Fr. Parker was quoted at length in the paper, talking about the importance of the library and the example this was of grassroots people being able to win. That you can take on city hall.

Then Detroit went bankrupt, and overnight the emergency manager closed every library branch except the downtown one.

There was an important lesson in there about power for a young organizer. Namely, that the old ways of mobilizing a single parish are probably not going to work any more, that there are forces out there more vast and indifferent than any of us can imagine, that we must grow, constantly grow, or be squashed.

It didn’t seem to bother Father Parker too much though. Obviously he had been witnessing the collapse of his neighborhood for a long time at this point. He talked me down when I was all worked up about it, and even gave a great, comforting, homily about it one Sunday. I think some of the lay people took it kind of hard, but Fr. Ted was a pastoral presence in the midst of this as he was in all things. Frankyl, worse things had happened in this parish. The closure of the library was but one of a thousand cuts. He continued showing up to organizing meetings. Still does to this day. I suspect, like many clergy and leaders of his generation, he does so often without hope that they will necessarily succeed, but rather because he feels duty bound to continue to show up. Duty bound to God and to his fellow man (where, of course, God resides as well).

Father Parker isn’t the last of a dying breed but he’s close to it. I don’t know if you’ve met any young Catholic priests lately, but most of them are verrrrrry different. The same goes for protestant pastors to an extent, and it’s my sense that it goes for leaders of people in any position, to one degree or another. I suppose one could say that I’m grieving the loss of left clergy and I suppose I am (left, not liberal. There’s a difference). After all, lefty priests (and nuns) were central to many of the great movements in American history, especially the peace movement and the civil rights movement. In Detroit, Father Parker is retiring, but Father Norm Thomas just died too, as did, most notably, Bishop Gumbleton, founder of Pax Christi. Brother Ray Stademeyer, my former pastor on the east side, left years ago. These guys certainly weren’t “left” on issues like gay marriage or abortion, but they were fervently in favor of economic redistribution, abolishing poverty and pro-peace. All of this informed by Catholic Social Teaching, where we learn that the basic moral test of a society is how its poorest and most vulnerable are treated, and that “the economy must serve people, not the other way around”. A valuable set of core principals which is forgotten too often today. These were left leaning leaders, but they put forth a leftism which didn’t bludgeon you, didn’t condescend to you, but rather lifted you and pulled you in.

If you meet a young priest today, they are very likely to be right wing. Some of them are outright Christian Nationalists. I have yet to meet a young Father Parker or Bishop Gumbleton. That’s a problem, in as far as it speaks to the narrowing of the ideological vision of the church, the lack of a hierarchy and clergy that is capable of speaking to humanity as a whole. But, as I’ve written elsewhere, I don’t have problem with conservatives per se. I love and admire many conservatives. When I feel sad about the loss of the Father Parkers of the world, the fact that he was far from a conservative is not what I grieve most. After all, I have a similar feeling about leaders of other institutions, including the mainline protestants, and their young pastors are mostly liberals (not leftists. There’s a difference).

No, what I miss about the old clergy is harder to put into words, but if I had to I would say it’s their humanism. Their love for humanity, in the broad sense of the whole world but also in the specifics of whoever the person was before them, whether they be the mayor or a homeless man. The sense that they felt called by God to serve us, people, actual, messy, broken people in all our glory. Not that they did it perfectly, but the fact that that was their goal.

When I see leaders of institutions, including, but not limited, to churches, now I feel that sense is going away. That somehow it is seen as old fashioned. These young priests aren’t chiefly frustrating because of their conservatism but rather because they seem to think their time should be mostly devoted to ivory tower style intellectual debates about the Vatican II or the latest papal encyclical. Many liberal protestant pastors seem to be mostly concerned with combing through the bible to find proof that Jesus was liberal, or that God is a woman, or some such thing. And the leaders of our political and civic institutions seem to spend more time trying to convince us that the other guy is bad, rather than what they are doing is good for us or our friends and neighbors. To me these seem like fools errands, like wild goose chases.

The lesson I learned from Father Parker is, at it’s core, that you should seek to love the person in front of you, and the community around you. That your actions as a Pastor, but really as person of faith, period, should be informed by that love, to the exclusion of basically everything else. Of course, the love of humanity and community means some things about how we should design society, but it’s the love that comes first, not the political theory. Nowadays I would call it the love of Christ, and looking back, I can see that Father Parker was filled with it. I could see it in his patience with me and with others, his commitment to his people and his city, and his willingness to go out and storm the ramparts again and again, even in a losing cause. I could see it in him dragging his weary body to another organizing meeting in the basement of the fellowship hall, and his calming presence when the meeting started.

And I could see it in the little sign at the side of the sanctuary at St. Cecilia that reads:

“In memory of all the American soldiers who died in Iraq. And of the over 500,000 Iraqi civilians killed”

But I could also see it in the cups of coffee he’d bring me, the arm he’d drape around the homeless woman or the elderly parishioner, his curious and twinkling eyes as he blessed our new baby.

I don’t know what will become of the Catholic clergy moving forward, I suspect the church is in for some tumultuous years. And I don’t know what is to become of our leadership class as a whole. Sometimes it feels hard to have much hope when you see the chuckleheads that have power over us. But I know we would do well to heed the lessons of this older generation of clergy. The lessons that the depth of your love and strength of your humanism are more important the logic of your argument or the books you have read. Perhaps we should start choosing our leaders on those timeworn criteria.

In the meantime, I hope to get down to Detroit to pay one last visit to Father Parker before he retires. It’s been a decade, but I’d love to have another long conversation with him, listen to his wisdom and tell him what he meant to me. How he is one of the good ones. Hopefully I can make it happen.

And who knows, maybe someday in a few years I’ll sit with him on a porch somewhere far from Detroit, out in the woods, by a lake, and reminisce. I’d enjoy nothing more. And even if society is collapsing around us, if the monster is at the gate and all seems lost, I suspect that someone down on their luck will find him, track him down on that porch, ask him for help. Whether he can help them or not, I know he’ll try, I know he will treat them with the love and dignity they deserve as a child of God. I’ll smile to see it.

This newsletter will always be free. Any paid subscriptions will be taken as donations to my organizing work in Michigan. If you would like to donate directly to that work, you can do so here. Thanks so much.

What a lovely tribute to Father Parker, both in these words and in the work you've done with him.

It doesn't fix anything in Detroit for me to say this, but it might be helpful to know that some of the problems with the church in the USA (i.e., both liberals and conservatives being much more invested in arguing for a correct theology that just happens to comport with their political opinions than in loving their fellow man) aren't problems in the same way in other parts of the world. I think there are far more priests worldwide who do emphasize putting the needs of the poor and vulnerable first, even if such rising priests aren't the most visible in the United States. For what it's worth, I think you would see a lot of the traits of Father Parker in our island's parish priest, who is quite some time away from retirement age.